Haptics by Melokuhle Mikelssen

In 2024, showcases for art echo early 1960s’ materiality. At that time a range of artists were emphasizing texture in many varieties. Turning from oils, acrylics, marble, bronze to more humble mediums, the creatives were as often engaging in material investigations and truth-in-form work as in preconceived compositions.

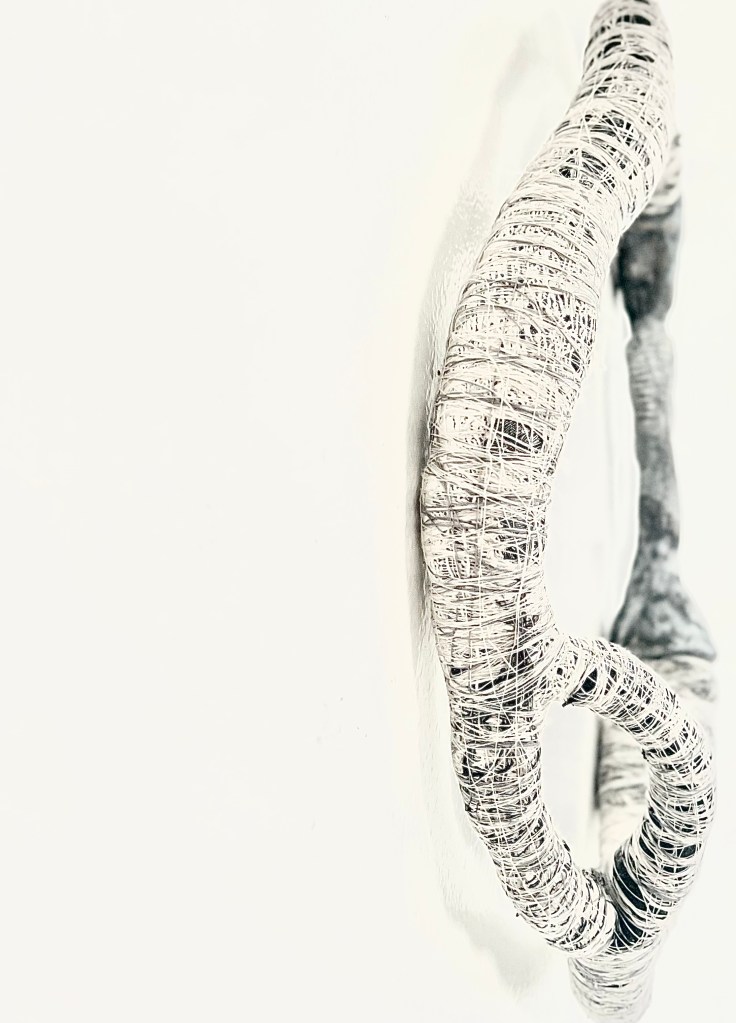

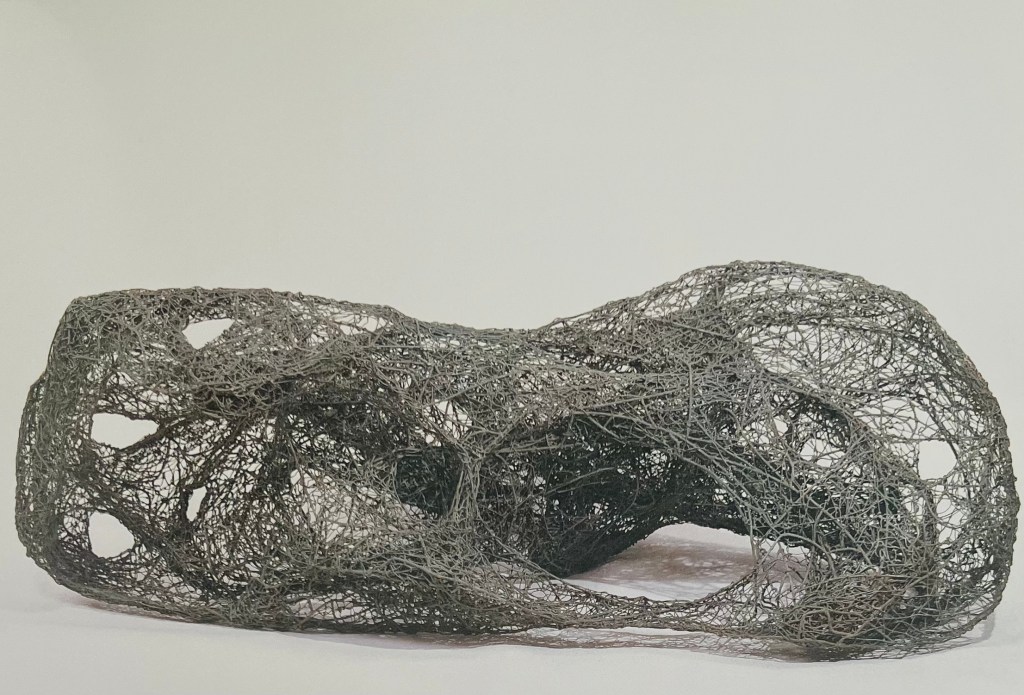

Exploring these materials— be they wire, rubber, fiber, textiles, earth materials, residential space, public art, movement arts, music— the artists worked in both two dimensions and three where a major component, if not the entire point, was texture. California clay artist John Mason slabbed work in 1961 reflecting this sensibility, as did a 1962 wire piece made in Paris by Claire Falkenstein. Manabu Mabe painted in Brazil, while in the early sixties Aaron Siskind traveled the US in search of peeling-wall patterns.

Sufficient work was being made that by the time the seventh São Paulo Bienal was being planned in the early 60s an obvious theme was materiality. The Brazilian expo counted among its 1963 selections rough or smooth pieces by Julius Schmidt and Chryssa. Robert Mallary displayed clothing hardened into impliability while Peter Agostino transformed malleable hygge such as a pillow into unyielding plaster objects. In North America Roosevelt Bassett reclaimed lath from house demolitions in Philadelphia to construct smooth, very solid variations of such typically-soft objects as hats, masks, and handbags. Textural considerations, tactile contrasts, crossmodal perceptions fed these works.

In Spain, Antoni Tàpies observed Franco erect ideological barriers as Barcelona walls accumulated both resistance graffiti and damage. Tàpies embraced matterism—lumber-applied impasto, additives such as grit— and moved into creating Siskind-looking walls from 40x40x20 slabs of lava on which he would slather earthen materials that could hold gashes, punctures, and grinding that conveyed the intended aesthetic.

The haptics under sixties consideration were apt for conveying change. Change from neglect, change from revolt, change from an era of relocating industries. Such rising industries as plastics or pharma located at road-transit sites while waning ones at city centers, railways, and water-transit sites led to unused piers, Manhattan abandoned factories, rust belt warehouse vacancies. These continue to be documented by Ukrainian now Great Lakes resident Mare Kovač, New Yorker Shaniqua Brown.

What the photos document, graffage interprets. An art juxtaposing the urban with nature, it might start with a meadow paved over or rust corroding once-impenetrable steel gates. Shirley Nette Williams of London is a graffagist describing urban materials’ reaction to nature by assembling clay and fiber components into haptic compositions informed by her dedicated photographic field studies. Sharp fissures in the facade were a recurring subject in Chicagoan Ruth Duckworth’s porcelain works. Zimbabwean sculptor Valerie Piraino combines textures of natural materials such as fruit with shells of citified glossy paint and nets of fiber. Plant fiber foraged in London, composed in ways informed by plant habit, provide visuotactile activation by Pip Rice. With manufactured materials Busan-based Hyun Sung Park might juxtapose pleated shards with loopy tubes in organic-industrial hybrids.

On a larger scale the haptics of space, light, shadow, and sound were explored in concrete by architects Jack Lynn and Ivor Smith. Their 1961 housing development Park Hill in Sheffield, like the 1971 Main Street Manhattan designs by Josep Sert, use curving forms to experiment with pedestrian vistas, with integrating flora into the urban grid.

At an intermediate scale of arts, sixties choreographers introduced an expanded vocabulary of movements, particularly the quotidian as antidote to the grand gesture of ballet. There was also an expanded vocabulary of music, including silence in which the footfall of the performers became a soundtrack. Rhythm too was associated with such formally percussive scores as Steve Reich’s Drumming accompanying Laura Dean’s dancers in 1975; the 1979 pulse of “Dance” scored by Philip Glass for choreographer Lucinda Childs within a set designed by Sol LeWitt.

The audiohaptics for percussion are well represented by composer Andrew Cyrille. Particularly his work in the 21st century in which he expands sonorics. After seven decades Cyrille launched recordings of his most exquisite rhythmic syntax. Starting with a 2016 release he has employed conversational improvisation in the studio and performance hall.

Cyrille’s dreamscape atmospherics of the 2020s have installation counterparts. The 2024 Gwangju Bienniale took as theme Music Of Lived Space. In haptic terms one of the artists, Hyeongsuk Kim, conveys corrosion associated with South Korean industrialized wasting in visuo-auditory components.

Haptic themes reaching from the earlier São Paulo Bienale include, at 2024 Manifesta exposition in Barcelona, Mike Nelson’s shack composed of materials found in an industrial brownfield, looking like a Donna Dennis work from a half century prior minus the whimsy.

In 2024 NY the Storefront For Art & Architecture exhibition of Galas Porras-Kim’s Alluvial Record displays a vitrine of wet Yucatán clay to humidify the gallery space, an environment activating the viewer’s pressure and thermal mechanoreceptors, bringing locale into subject matter.

Kim-Yang Lin formed a NY troupe in 1988. His choreography alternates fluid with syncopated kinetics in thematically lucid works such as the 2011 “Mandala,” performed most recently in 2024 FringeArts. The troupe’s textiles are integral to a performance’s ductility.

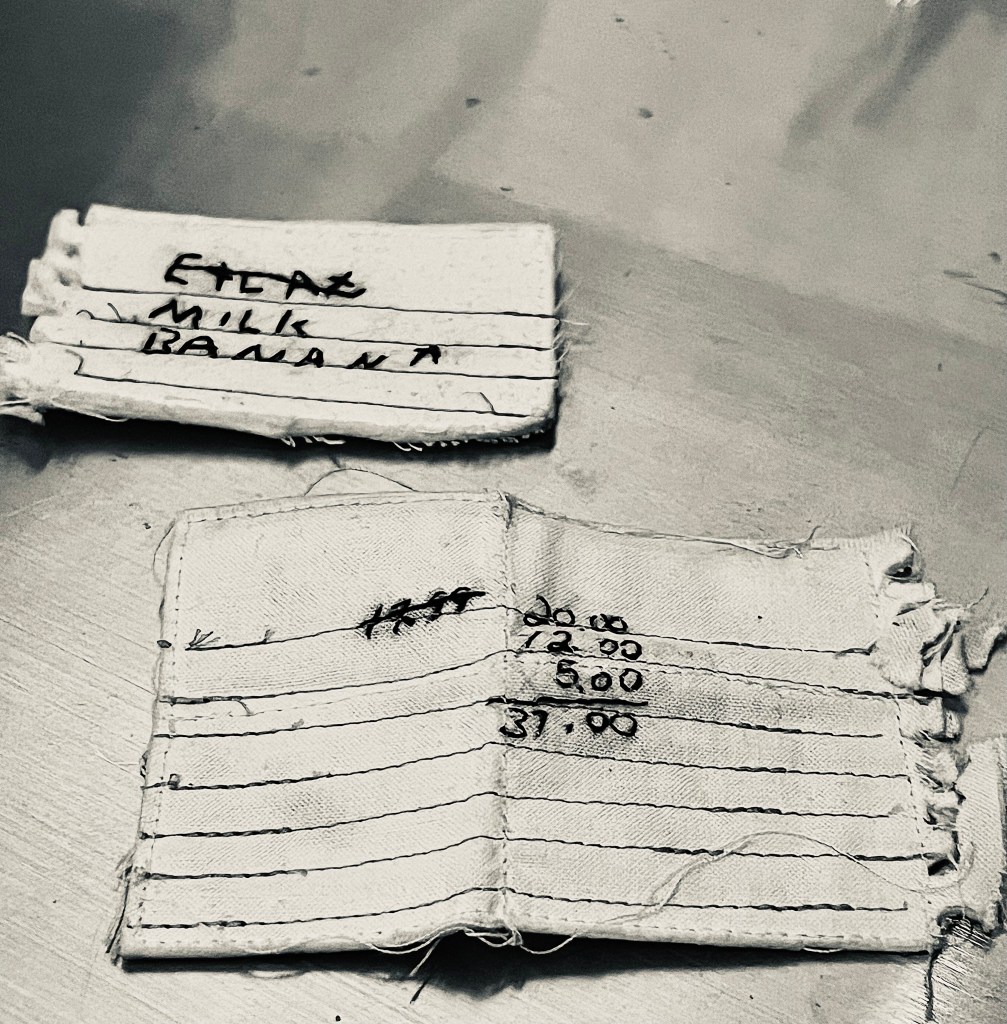

Fluidity, softness, tactual triggers in sculpture contemporary and recent. A graffagist using improvisational recombination, Bergen-based Cato Løland assembles found scraps of manufactured material into sculpture informed by the gendered economics of apparel. US midwesterner Douglas Dale interprets hard in soft terms, transmuting the features of solid objects to fuzziness, hard-edge to fluidity. Shannyn Reid of Newfoundland shifts soft subjects into softer matter; her textile shopping lists and oversized shopping bags offer a wry commentary on the banality, the environmentalism of consumerism. Ursula Burghardt toyed in Cologne with concepts of softness in materiality, recreating, as an example, clothing in industrial materials.

Middle ranges between soft and hard are explored in Londoner Beverly Ayling-Smith’s manipulations of fabric: tearing, stitching, staining to represent scarification. Chicagoan Robert Burnier manipulates aluminum as if fabric into wall sculptures. Soft and sharp are combined by Anchorage-based Sonya Kelliher-Combs fiber&pin works from the recent Shedding Skin series that abstracts the tusk shapes that have served her as repositories for the subconscious. Pliability as well as scale feature in Brazilian Lidia Lisboa’s sculptures. Fooling the tactile sense and thermoreceptors are Bahamian NYer Anina Major works looking like aged basketry, feeling coolly ceramic.

With the cross-sensory nature of texture come cycle-of-life associations. The content, the materiality— these may remind of biological emergence, burgeoning, deterioration, seeding. Or industrial cycles of invention, extraction, malignant propagation, decline. Cultural traditions across the globe fall into this area, saudade, mono no aware, hiraeth. In the realm of haptics the word feeling applies to affect and anatomy both.