US Abstraction by Mabel Carver

Compositions abstracted from the world or expressively surreal or nonobjectively mathematical— these hold an enduring place in the history of US artists. Simultaneous clapping in varied tempi, improvisations in scores for chamber orchestras, choreography reductive from gesture, emotive without subject matter. Films divorced from narrative, derived from geometrical principles. Architecture emphasizing light or sonics or scale minus ornamentation.

Such intellectual exercises reassess underlying art principles, especially form, for 20th and 21st century US art, much like American law distills principles like equity, liability, rights from specific actions. The exercises then beg the question what, beyond the traditional illustration, can art be?

Nonrepresentational work has a legacy continuing through the present age. For painting, Norman Lewis midcentury works precede Mark Bradford Venice Biennale wall pieces. Roy DeCarava’s abstracted 60s pictorials feed LaShonda Stokes’ twenties while photographic lineage continues from 1977 Herbert G. Wheeler to 2002 Kira Lynn Harris. In sculpture a line might be conceived between the long series of welded pieces begun in the early sixties by Harold Cousins or Melvin Edwards to twenties works by Abigail Lucien.

Landscape design throughout this period has been an arena for artists to advance spatial apperception or well-being in public spaces. Experiencing kinesthetic stimuli in new ways; recognizing new corners of the civic environment; activating open spaces for prosocial activity. These motives drew US artists not only toward land arts of the sixties but also addressing such urban ills as under-maintained pedestrian corridors.

J. Max Bond-designed the 1978 Schomburg Center to expand research opportunities and a range of arts venues. He included street-grid engagement and a pedestrian courtyard. This is in contrast to David Adjaye’s 2021 Winter Park Library in Orlando, which is situated on a green interlaced with park and pond walkways. Urban pedestrianism was a focus for early-seventies Smokehouse Associates, who didn’t create buildings but used outdoor sculpture with hard-edge painting to reclaim alleyways, derelict parklets, and vacant demolition lots.

Unlike mural programs that situated high for placemarking monumentality, Smokehouse used a 15-foot maximum in the early seventies to enhance on-foot activities like errands, constitutionals, travel to work, visits to play areas. Through a series of neighborhood interviews and site planning, designs were assigned palettes from vicinity retail displays, arranged to focus on specific sites for rest, contemplation, meeting, play. Outdoor rooms, as it were. The motifs might reprise at stoops or doorways along a route to emphasize the walking journey.

The spirit of experimentation and improvisation that dwelt within abstractionists was encouraged in various decades by some venues, Riverside Museum, Just Above Midtown gallery, Westbeth public space among the galleries welcoming new thinking. In three dimensional work diverse mediums were seen. From the 70s Maren Hassinger has employed jetsam; in the 21st century she utilizied her fiberwork training for works of woven newsprint. Since the early 70s Barbara Chase-Riboud works with earth materials to create bronze casting, eventually incorporating a signature draping of fiber clusters from monument-scaled sculpture. Born in the early 70s, Leonardo Benzant has explored similar suspensions with the medium of beads. Same cohort includes Chicago sculptor Nnenna Okore who creates clay beads to be woven into relief. A decade younger, Allison Janae Hamilton has created works in feathers. Still a decade younger than that, Cameron Clayborn’s sculptures have included stuffed textiles as a base for other mediums.

An early series for Stephanie J. Woods was woven body gear, while wood sculptor Thaddeus Mosley often sources trees from which he can create monument-sized works. Frederick Eversley has used the medium of resin for creating prismatic monoliths that activate a space with refracted light in addition to form.

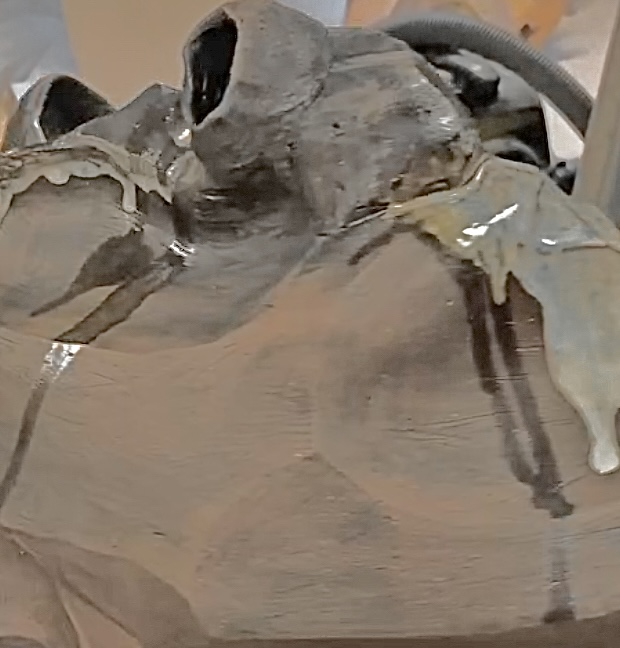

Howard Smith applied his abstract compositions in prints to ceramic forms in the seventies and beyond. His abstractions were surface design, while some current clay artists have developed texture or form to give expression to the concepts. Donte K. Hayes uses inscribing, allusive to the America-specific pineapple symbol, to convey his research in national history. The slab-built box form has been an endlessly fruitful motif for Paul S. Briggs to convey a variety of ideas about American character. For Gerald A. Brown formal composition combines with unpredictability of glaze, giving organic forms otherworldly characteristics that embody her futurist side.

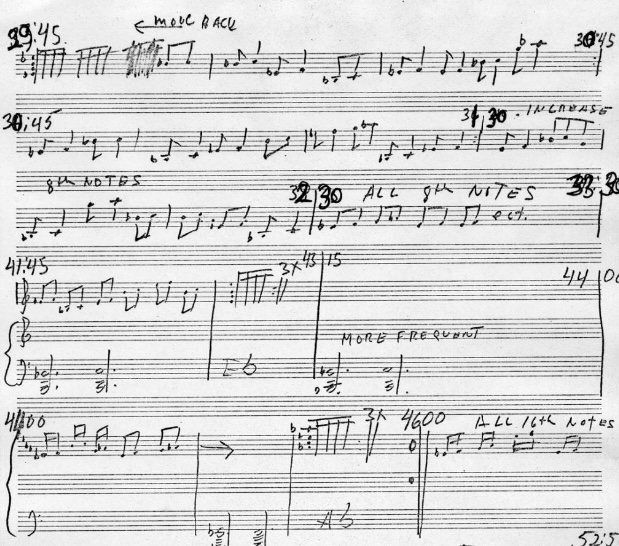

Abstraction in music throughout this period was often reassessing armature; it explored repetition, sounds of modern life were addressed, sometimes the nature of recording was a mode of expression. To inject more of 20th century social concerns and to broaden the US historical context of the canon, a composer like Julius Eastman applied conversational improvisation to pulse. As a player-composer he seemed to enjoy putting chamber groups into open-ended circumstances where performances of the score varied substantially.

Faculty member at University of Buffalo, Eastman was a member of Creative Associates and SEM Ensemble which periodically put him on the performing circuit of Albright-Knox Museum/Carnegie Manhattan/Rutgers University from the late 60s to mid70s. These experiences prompted him to relocate to Manhattan where he was associated with the Brooklyn Philharmonia and its Community Concert from the late 70s to early 80s as well as with The Kitchen and the Third Street Music School for 3rd stream experimentation.

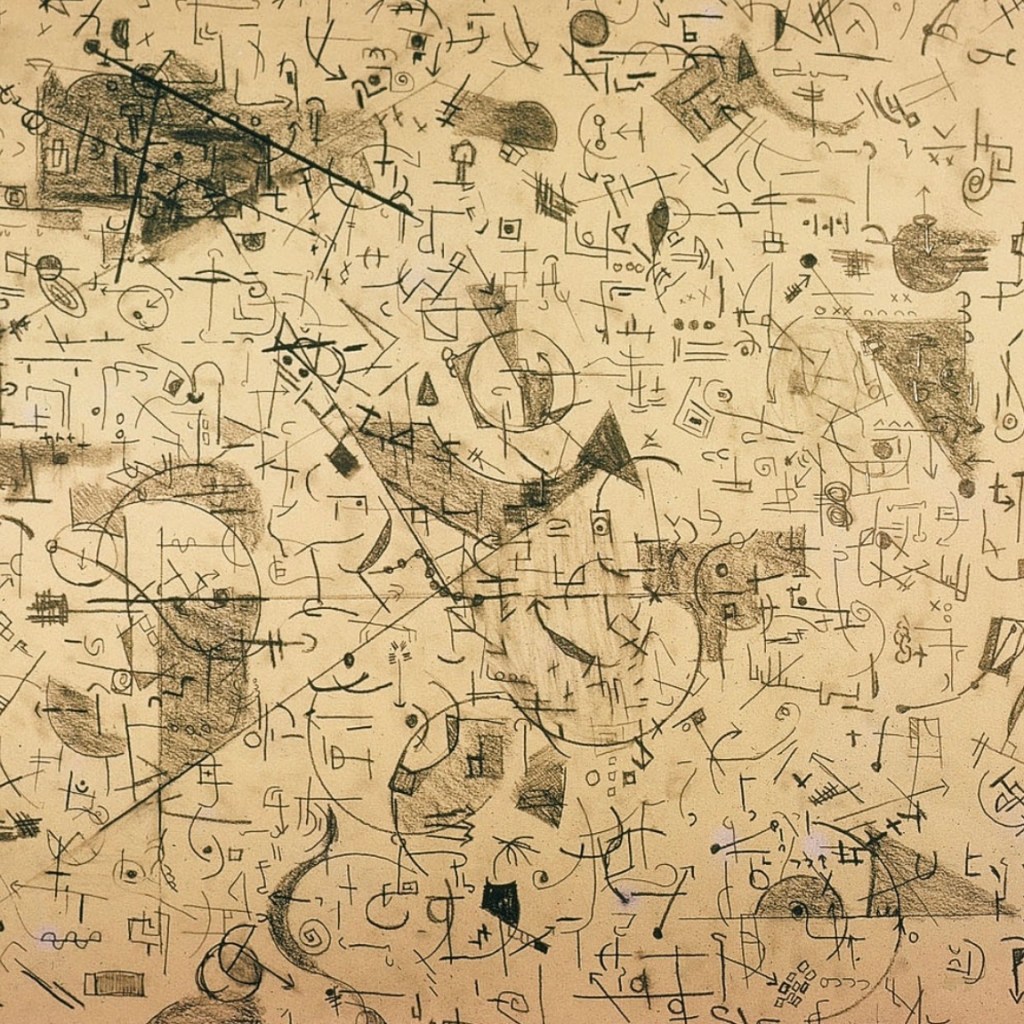

Such experimentation included sparse scores for a masterwork like Femenine, one-page scores for others that resembled the art of asemic writing and similar imagined abstractions, for example Cynthia Hawkins’ hierog series on paper of the same years. A nineties series of handmade-paper reliefs by Helen Ramsaran even further abstracts primal tones; a set of 10 paper works, collage-and-drawing, create an imagined pictographic score by Jennie C. Jones.

Consideration of abstract performing arts might include the 1934 premiere of the opera Four Saints In Three Acts. Amidst a score by Virgil Thomson, sets by Florine Stettheimer, choreography by Frederick Ashton, arranger Eva Jessye gave life to the stream-of-consciousness libretto of Gertrude Stein. The sixties’ choreography called contact improvisation was explored by Ishmael Houston-Jones in the eighties incorporating random triggers for actions that would vary from performance to performance, from dancer to dancer. Lauren Putty employed individual and conversational improvisation into Putty Dance Group’s performances to jazz compositions by Brent White staged live before the musicians such as the piece “Glimpse” at Neighborhood House Philadelphia, 2024.

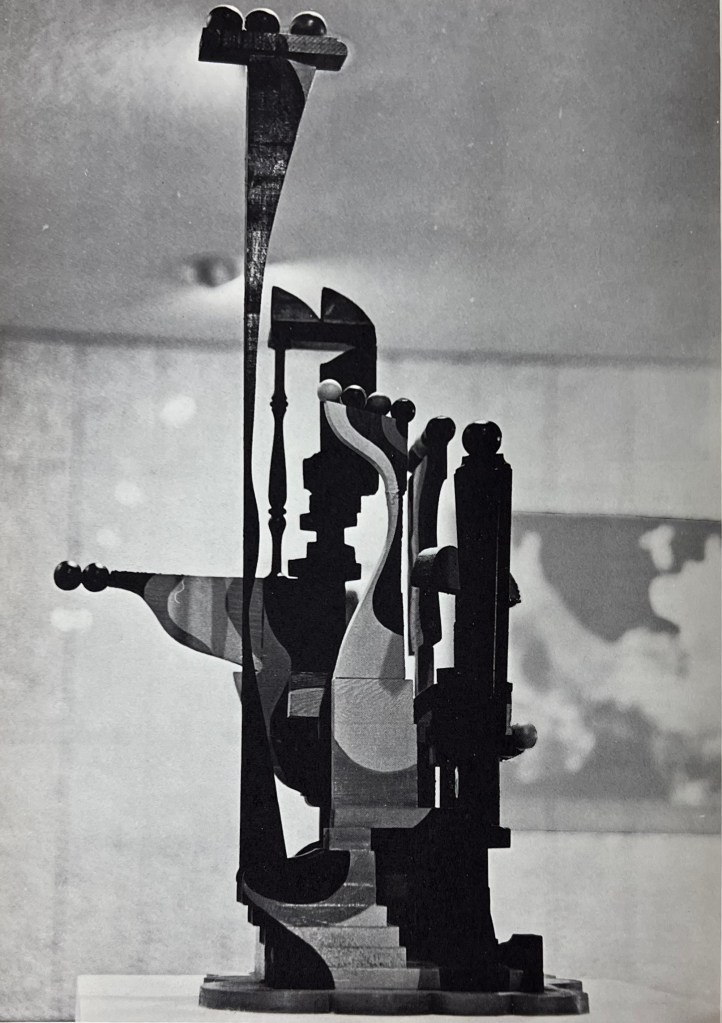

Mise-en-scène has Edward Owens’ films sharing compositional territory with Brown’s clay works, whereby collaged body parts, smoky tones, indefinite orientation create poetic, ambiguous visuals. Intertwining components also feature in Juan Logan’s early-seventies steel sculptures, as well as Ibibio Fundi wood works and Ralph Arnold print-making from the same period. Relational components, figure-ground variety, was a consideration for canvas painter Ellsworth Ausby who eschewed stretched textiles, using instead shaped canvas substrates hung tapestry-style.

Such range— of process, mediums, content— in the realm of abstract arts from the World War/Cold War era through the current period suggests not only that US abstraction will thrive to a centennial mark but that the nation is gifted with representatives of this national heritage exhibiting as octogenarians: Chase-Riboud, Ramsaran, Eversley, Mosley (actually a nonagenarian). These elders provide abundant inspiration and points of departure for recent practitioners.

Cover image: Paul S. Briggs