Assemblage by Echs Wye

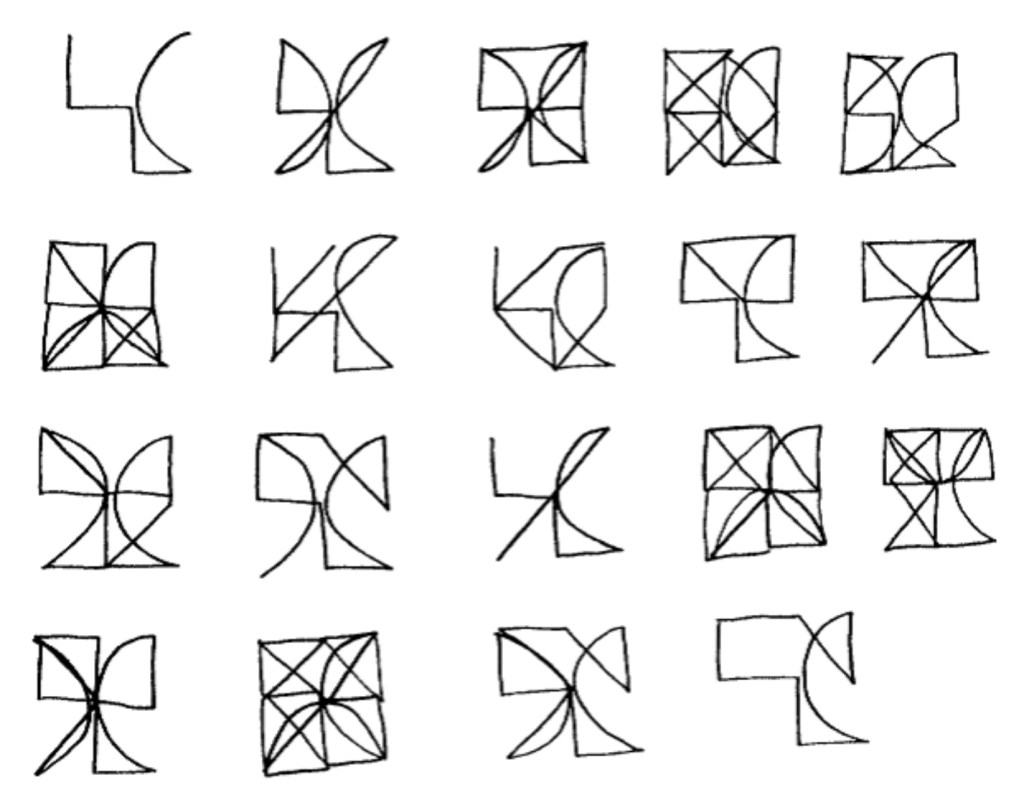

The visual art of arranging found materials— broader than generally recognized? Collaged paper and assemblage sculpture hang alongside mosaic, welding, tableaux. Basketry, wrapping, bricolage. Quilting not limited to piecework, appliqué, trapunto.

High-concept, process-driven practitioners include some artists not participating with the commercial art gallery. Hammons in contrast to Hesse, say. This may be one of several reasons for obscurity, another being the tastes of the commercial gallerist or auctioneer. In assemblage the very materiality of remains suggests marginalization even while the creative process of accumulation can suggest resilience, repurposefulness.

Feeding the conceptualism were diverse sources. From Albers’ Yale material studies to post-war Polish innovations in fiberwork, countercolonialism artists in South America to west coast basketry developments.

Following Art Informel and El Paso of the fifties and roughly contemporaneous to Arte Povera and Mono Ha, Los Angelenos as well as New Yorkers employed a range of materials with which to compose works, creating two hubs of assemblage in the US.

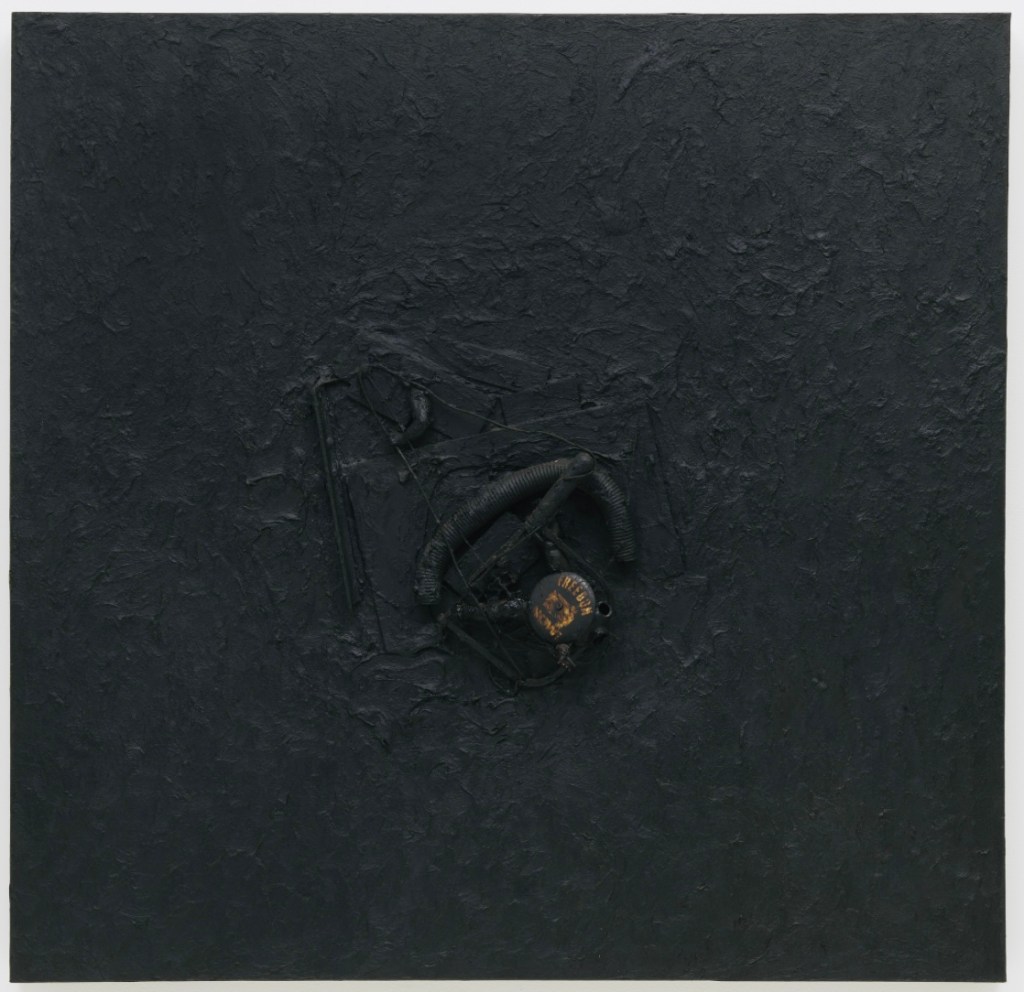

The West Coast group had a physical locus in the Watts Towers begun in the twenties by assemblagist-mosaicist Simon Rodia. It became a community arts center. John Outerbridge, who worked as director of the center for years, produced among other works a striking series of stuffed textile assemblages. Daniel LaRue Johnson used tar, as in tar-and-feathers, to make monochromatic assemblages to convey his thoughts about oppression.

In New York Randy Williams created assemblaged reliefs while Jack Whitten pursued an increasing attempt to get away from the brush in paintings that mosaiced dried, cut acrylic skins. Alice Adams, before shifting in the 80s into landscape art, made assemblages in a series of material investigations. Taking mediums from the pier-related businesses of lower Hudson Manhattan, Jackie Winsor made heavy, human-scaled sculptures. Having fled Nazism to the Bronx, Hannelore Baron became a self-taught collagist who also developed a series of objet assemblage.

More recently, assembled works by Veronica Ryan of Manhattan often employ botanical elements for historical references in abstract works. Viyé Diba of Senegal utilizes a variety of objet trouvè to give dimensionality to environmentally-themed paintings. Massed-material sculpture by Leonardo Drew in Brooklyn can present in room-scaled installations.

In the realm of quilt-derived arts Anna Wagner Ott of Ottawa used a wide range of shaping techniques in her textile-based works. In addition to wall- or floor-based assemblage Charles McGill of New York created quilts of unconventional materials such as deconstructed golf bags. Trapunto patterns offer dimensionality and shadow play in the quilting of Leeds artist Ruth Singer.

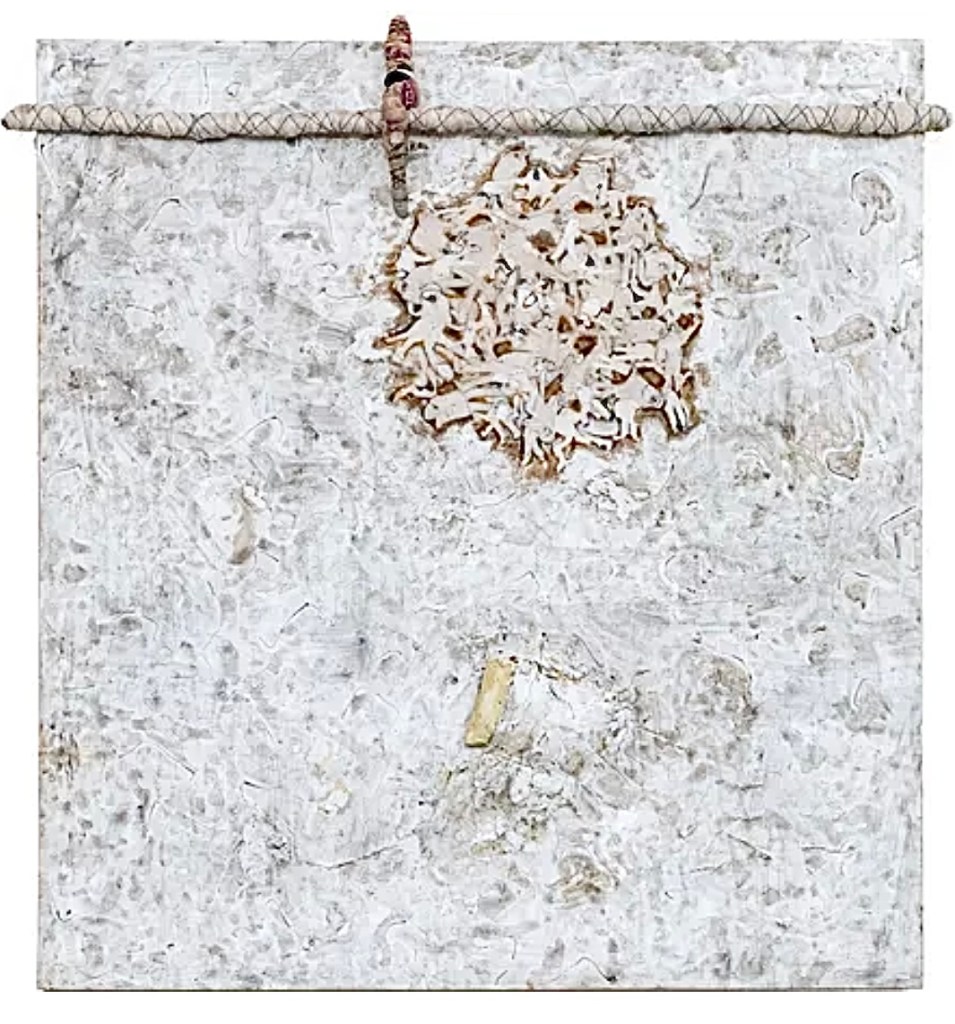

Basketry of foraged and prepared materials as well as found objects represent a form of assemblage familiar even outside art circles. Boulder artist C. Maxx Stevens draws on family background. West Yorkshire’s Alice Fox, known for inventive embroidered attaching, has also created off-wall assemblages that include plaited materials. A form related to basketry, wrapping, includes three-dimensional works by Arthur Simms in Staten Island as well as more two-dimensional, optical wall pieces wrapped by Emil Lukas in Allentown. Related knotting works with impact were made by Swiss Francoise Grossen.

Even greater three-dimensionality is on offer in choreographic assemblage. Moving from what Yvonne Rainer termed the heroic posturing of ballet-derived performances, the years around 1961 that saw the brief life of Judson Dance Group in New York led to layering quotidian movements. This was practiced by Grand Union and individual choreographers such as Trisha Brown. A related genre involving Cagean chance or improvised steps such as Steve Paxton’s contact improvisation quickly dispersed through the dance world. At times dancers pigmented body parts to create records of their kinetics on cloth or paper.

In space beyond that of the stage, assemblage applies to vernacular building styles like Watts Towers, for example, as well as the architectural case of the annex. As with sculptural assemblage, juxtapositions may serve to reinforce or contradict. Contrast is the case for Neue Staatsgalerie in Stuttgard, designed by Londoner James Stirling, in 1980 as well as Lille’s Le Fresnoy Art Center by Swiss Bernard Tschumi in 1991.

Outside of three dimensions, assemblage has been employed by composers in ways from musique concrete to micromontage. Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Konkrete Etüde is an example of the former employed with prepared instruments. Horacio Vaggione and Iannis Xenakis used the granular composing techniques permitted by electroacoustical equipment to forge cogent musical works (Schall and Bohor, respectively).

Writing styles related to assemblage include list prose, cento mosaicism, erasure poetry.

In film, montage has been a long-studied arena with time a component granted artistic and sociopolitical qualities. From the twenties collaged images of Joris Ivens and Ralph Steiner to Chantal Akerman’s feminist tempos, the aggregation of images into mood, concept, or moment has been used for art and entertainment both. Among the more viewed films effective with soundtracked montage, both dream sequences, are Vampyr (1931) and Rosemary’s Baby (1968). Related to film montage would be the gallery-sited photocollage, for example Philipp Eichhorn of Basel or Mary Ruefle of Vermont.

Textile collage includes practitioners Alicia Henry of Nashville, Samuel Levi Jones of Indianapolis, Jakkai Siributr of Bangkok. Textiles also figure in the bundled works of such artists as Daniel Graffin of Paris, Sonia Gomes of São Paulo.

The site of assemblage sculpture varies. The wall, in the case of Japanese-NYer Yuji Agematsu or Brooklyn’s Kennedy Yanko or Caracas’ Federico Ovalles. The ceiling, a la Cameroonian Pascale Marthine Tayou. The floor or wall, for Guadalajara resident Jose Davila. The pedestal, for Bellingham’s Tanis S’eitlin. Installations, for Tokyo’s Yuko Mohri.

Cover image: Alice Fox