Iberoamerican Geometries by Adina Alves

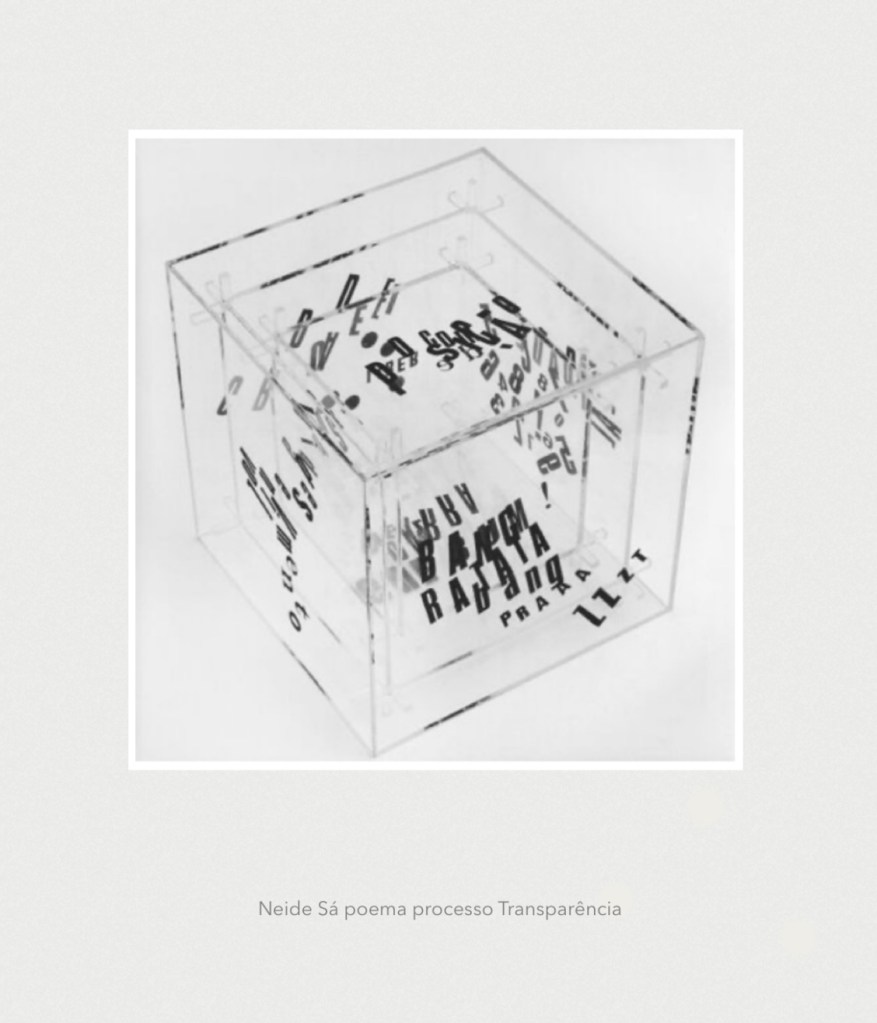

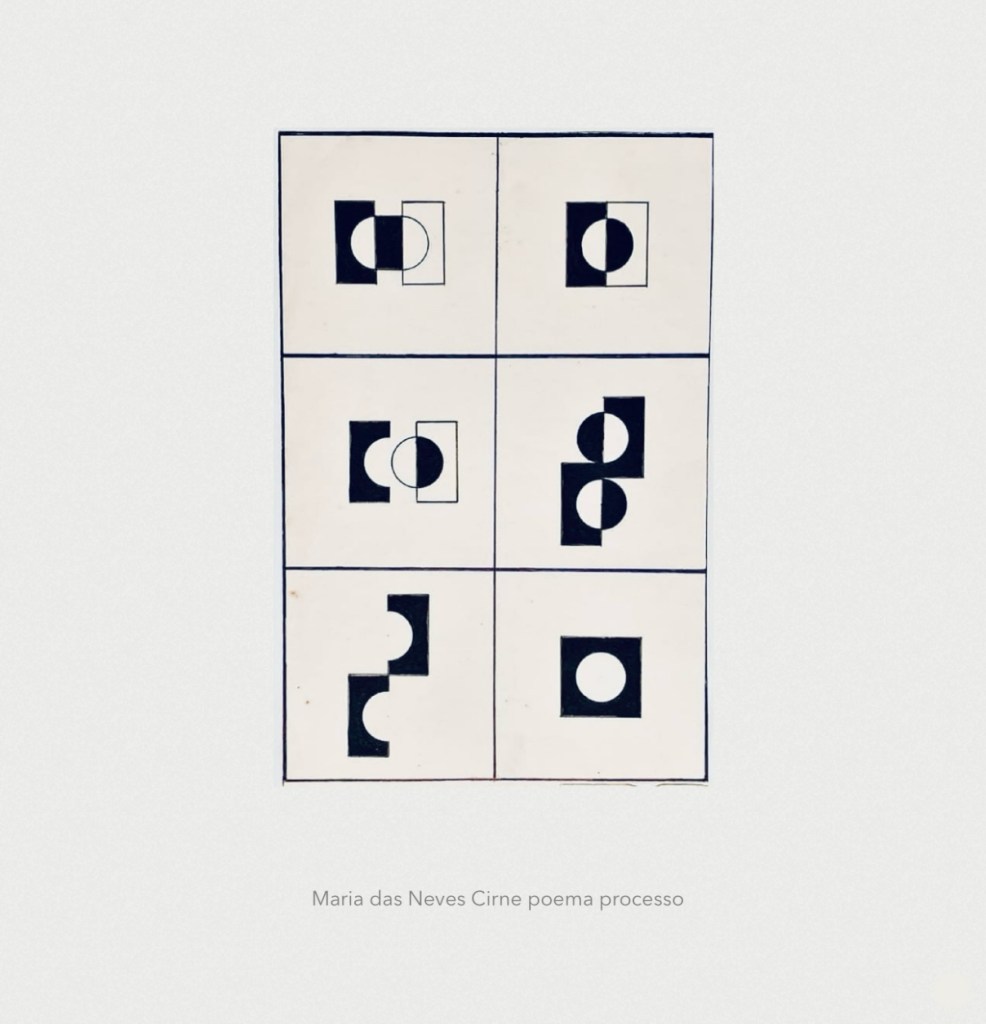

In South America, geometric visuals have been partnered with textual material (concrete poetry, visuopoems) often through the materiality of process art. One result was Poema/Processo works of the postWWII period. The Brazilian variety reached audiences via periodicals from Montevideo and installations in Buenos Aires or Rio de Janeiro. It was shut down in Brazil by early 70s police interventions.

Fulvia Lopes, Brazil

Neide Sá, Brazil

Lenora de Barros, Brazil

Maria das Neves Cirne, Brazil

Inez Silverman, Uruguay

Anna Bella Geiger, Brazil

Mira Schendel, Brazil

Emilia Azcarate, Venezuela

Jac Leirner, Brazil

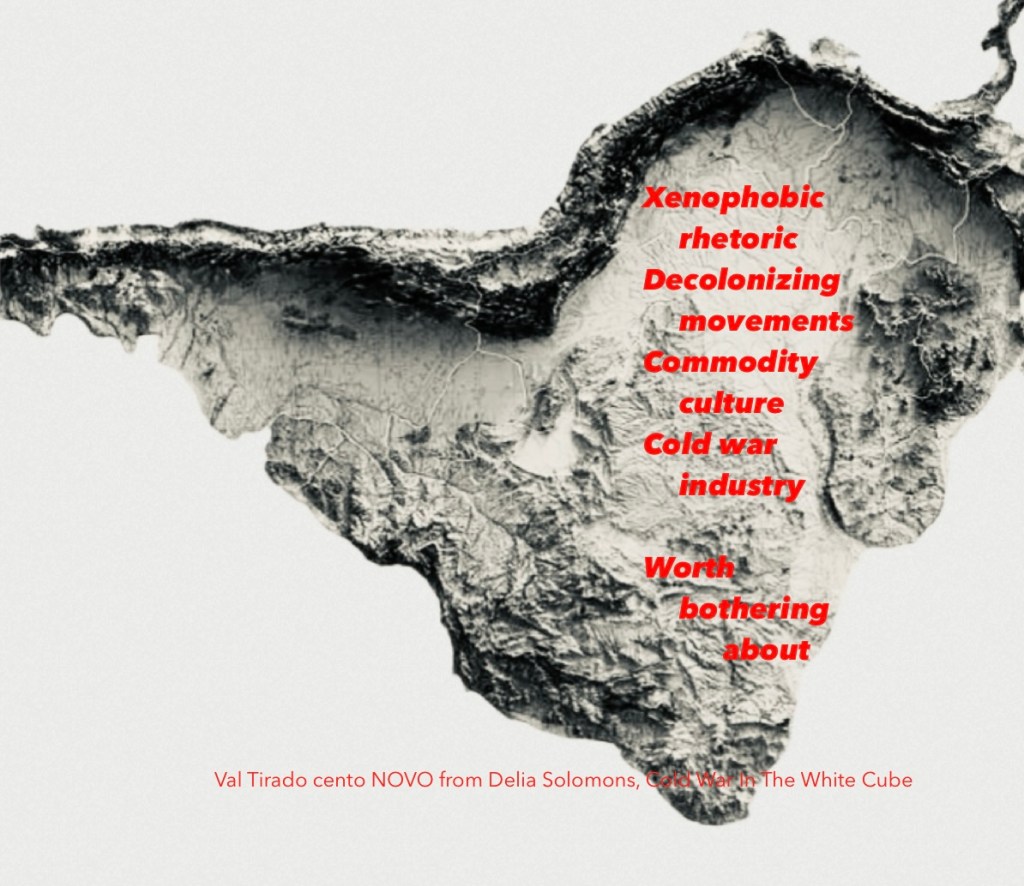

Val Tirado, Ururguay

The visual aspects that made the Poema/Processo distinct had developed amidst varied Iberoamerican influences. Andean graphic reductives or bahian-afro assemblage; rioplatense gestural abstraction or Atlantic capricornic constructivism. Social currents eddied, for example suffrage occurring postWWII in the larger nations, in the 50s for Peru, Bolivia, Columbia. These South American caches fed into midcentury geometric arts and renewed across subsequent decades.

Cold war economics made geometrics regionally visible. Museum-building in Buenos Aires, privately funded, and in São Paolo, Rockefeller-backed, provided institutional visibility. Rockefeller-backed traveling exhibitions on US museum circuits gained glossy press coverage circulating back in magazines and newspapers.

European artists who had fled Nazism to South America were particularly active in Argentina, while young Uruguyan artists across the Rio de la Plata developed less esoteric religious or philosophical bases for reductive art. Industry informed arte concreto more than medieval scholastics. The Buenos Aires magazine Nueva Visión began circulating in 1951 to consider the Montevideo and Argentinian developments. A nonobjective exhibition was mounted in Montevideo within a year, Maria Freire prominent among the artists showing. She went on to participate in the 1953 and 1957 São Paulo Biennal.

Young artists not privileged with European or NY stints became modernistically inspired on home grounds.

Myriam Montoya, Columbia

Mariana Copello, Venezuela

Gihan Tubbeh, Peru

Fernanda Gomes, Brazil

Amelia Toledo, Brazil

Noemi Escandell, Argentina

Lidy Prati, Argentina

Lorena Velasco, Columbia

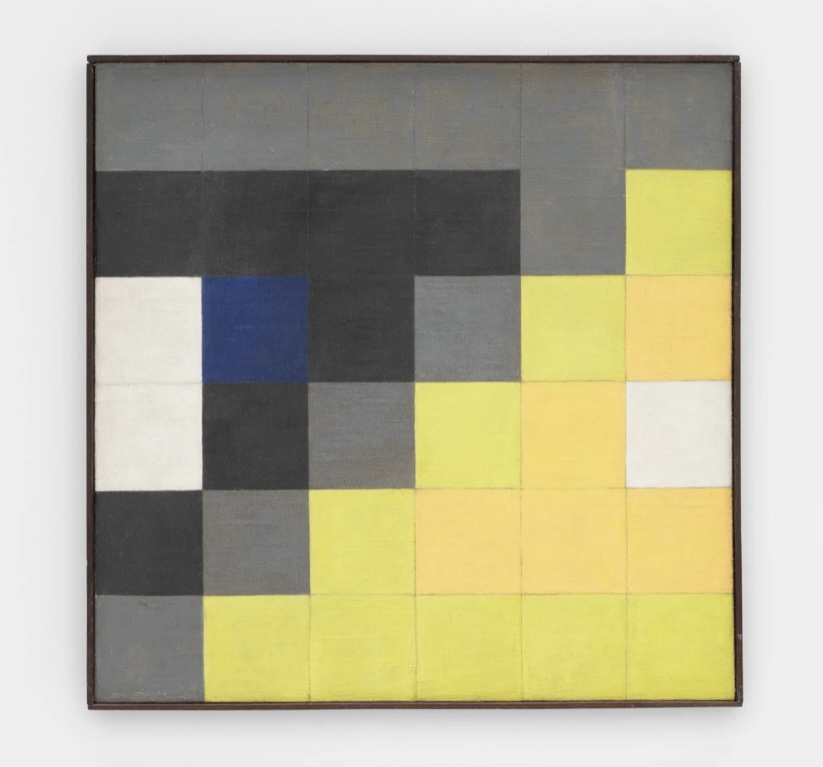

Maria Freire, Uruguay

Lélia Coelho Frota, Brazil

Luisa Duarte, Venezuela

Bruna Machado, Uruguay

Violeta Orozco, Mexico

Judith Lauand, Brazil

Gisele Camargo, Brazil

So although the US CIA strategy deploying exhibitions for propagandistic soft diplomacy or Rockefeller use of MOMA resources to stabilize interests in Standard Fruit, Standard Oil, or bank-lending reflected the nonaesthetic side of art economics, some curators, critics, and most importantly artists tapped into these currents to cultivate art geometrics. Geometrics in turn were adopted by Brazilian leadership to represent a nonobjective future. A future of expanding political independence. Expanding economic power. A new capital, Brasilia.

Celeste Suarez, Uruguay

Florence Goupil, Peru

Sandra Barclays, Peru

Alicia Haber, Uruguay

Rocio Romero, Chile

Lyda Caldas, Columbia

Brasilia was intended to reflect its country’s assuming the mantle of continental leader, eclipsing Argentina’s cultural heritage. Brazil intended to clear a path design-wise, economy-wise, art-wise. It funded a Bienale in São Paulo to create a global arena. Brazil publicized its willingness for trade, for alliances in contrast to Argentina’s neutral-to-isolationist leanings during dictatorship struggles, missile crises, extracontinental backing of various anticommunist, even autocratic regimes.

In Caracas, the Venezuelan context was an expanding economy with less of the symbolism of Brasilia, less of the sociophilosophical goals of Argentina. A desire to establish global trade opportunities postWWII was paralleled by an interest in establishing international art relations. An expansion from a midcentury oil boom enabled Caracas and Buenos Aires artists to mount geometric exhibits at the new Taller Libre de Arte while Venezuelan artists in Paris launched the periodical Los Disidentes. An artist like Gego could break from the optical-art abstractions of Caracas modernism to create sculptural geometries that grew to room-sized proportions.

Gabriela Lena Frank, Peruvian American

Adela Zamudio, Bolivia

Adina Izarra, Venezuela

Josefina Plá, Paraguay

Cassi Anranches, Brazil

Despite varied international relations, despite internal political preferences, concrete art arose in Montevideo, Buenos Aires, São Paulo and elsewhere. In midcentury it was a fairly eastern genre in distinction to the figurative pursuits of the Bolivarian nations, Santiago surrealism, caribbean portaiture. However, there were thematic connections to precolumbian abstraction such as amazonian casarabe glyphs, andean quipu, pacific Moche motifs. And Arte Concreto fed geometrics back into post-concrete work, informalism, assemblage, and reductive works across the continent that have made the past 50 years of modernist art so vibrant.

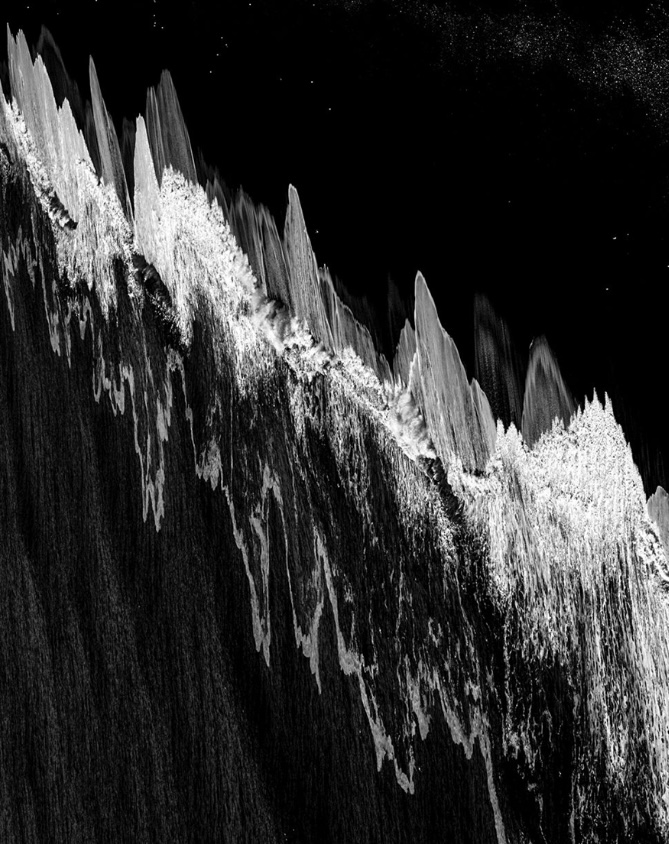

Cover image: Martha Boto