Hard Strung by Irwin Freeman

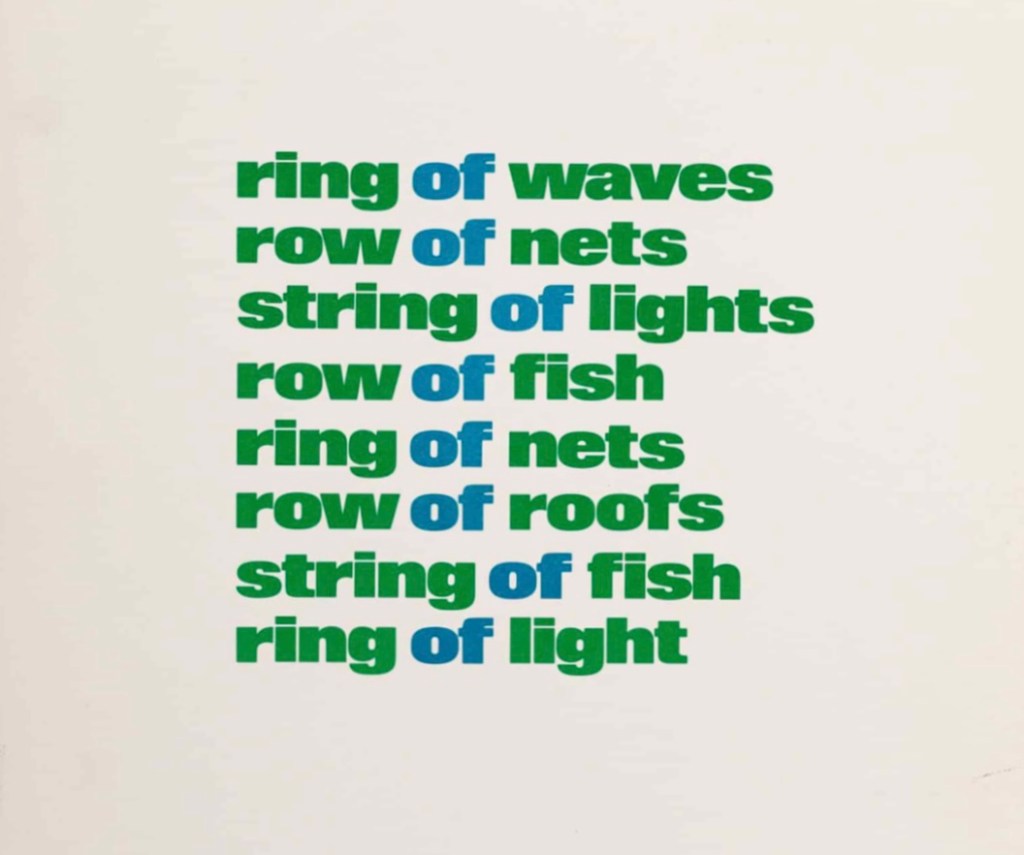

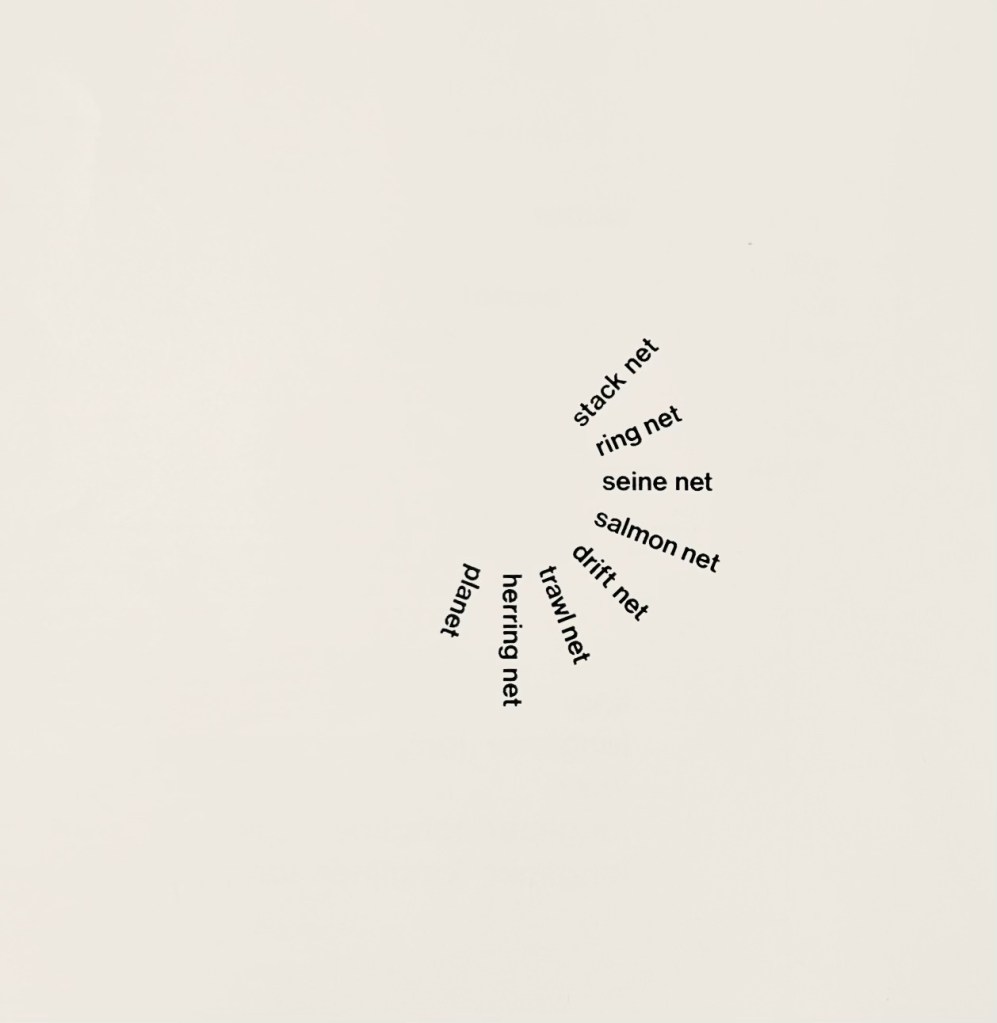

Fiberwork sculpture over the last ten decades has developed into a genre for individual expression. That it emerges from utilitarian roots, often gender-aligned, is a persisting trope in writings on the subject. Among the gender-based traditions we observe are cooking baskets made by Ye’kuana men on the Orinoco, baby baskets constructed by expectant Pomo fathers of California. 19th century Neopolitan basketmaking guilds apprenticed the sons of villagers, Frenchmen on stilts tended grazing sheep while spinning the wool and knitting it into socks. Generations of nautical cordwork was made throughout Canada, from troller nets by Newfoundland fishermen to decorative, crochetesque marlinspike seamanship of sailors on leave in Vancouver. Aquatic traps have been woven by men from Vietnamese fishtraps in the northern hemisphere to Maori eelpots of New Zealand in the southern.

Eight examples of culturebound works. Parameters of form were set by tradition rather than by handcrafter. The maker yielded to generations of expectation. Over the last century, however, innovation as permitted by fine arts lets us read of new mediums, lets us see originality on gallery pedestals. At least intermittently.

During that century of innovation, fiberwork received so little critical attention that it periodically is declared in revival. Traditions— expanded, if not abandoned. A century ago the noteworthy development might have been the move away from traditional pattern to idiosyncratic compostion. Surface design. A half-century ago the development would’ve been expansion of fiber types. Material investigations. In the 21st century greater attention goes to content, particularly political messaging. Process remains a neglected subject. Distinctions between types of fiberwork, vague.

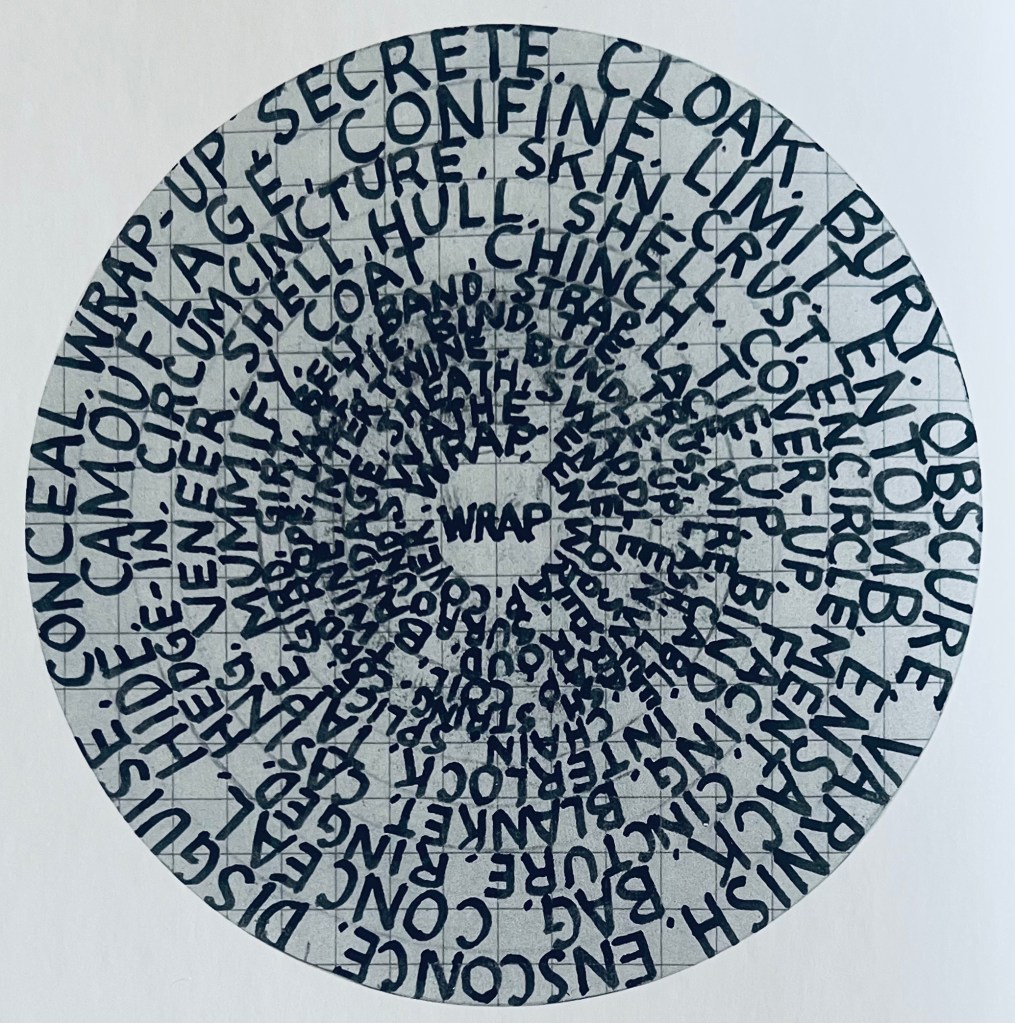

It may be helpful to our appreciation if we mark some of these distinctions. The first might be that fiberwork by virtue of its starting point the strand is not textile art. The latter uses prefabricated sheets of fabric. A second is the definition of fiber, in this setting a nonmetal strand that does not hold a bend. A third distinction would be sculpture type, planar versus volumetric work. Planar works, grid-based and employing euclidean geometry, are familiar from weavings, knit panels, macrame reliefs. Volumetric works exploit noneuclidean geometries, spirality, and torsion to achieve three-dimensionality. Basketry is an instance brought readily to mind.

Planar works can be displayed sculpturally yet are different from volumetric works that are built to resist gravity. Planar sculpture uses armature, volumetric sculpture uses tension. A planar work absent the suspension cables, the metal frame, the stuffing, or the fixative would pool on the floor. A volumetric work would maintain the sculptural form that is intrinsic to its construction through the pull of isometric connections between knots.

Examples illustrate the differences. Such planar works as beaded textiles, knit garments, woven tapestries can be hung a la paintings on the wall, they may be suspended from the ceiling to be viewed from both sides, they may be draped over a mannequin. They can be attached tentlike to frames to create varying degrees of three dimensionality, or fixed with resin, or stuffed then stitched closed. The sculptural form in each case derives from armature.

In contrast, a geodesic dome exemplifies the self-supporting tensions of such volumetric fiberwork as the 20th century tradition of bambooworking in Japan. Hisako Sekijima, Hideho Tanaka, Yako Hodo produce exquisite compositions in which fibrous tension and suspension are captured. The practice developed postWWII to involve apprenticeship over years, works sometimes occuring at a rate of one piece annually. Achievement in bambooworking may be nationally recognized with honorifics. Noboru Fujinuma has been designated by Japan as a Living National Treasure for his body of works.

These three-dimensional sculptures can be made at a scale of maker’s head, reduced to fingernail-sized, or magnified beyond monument scale. The outdoor branch structures of North Carolina-based Patrick Dougherty use edificial properties. Tomas Saraceno, Argentinian architect working in Germany, produces room-sized architectural models of meshes based on such arachnid research as laser-mapped spiderwebs farmed in plexiglass cubes housing black widows. His speculative models anticipate, like Buckminster Fuller’s domes, a future use for these as-yet impracticable dwellings. They experiment with tension-based oblique angles. The models are interdisciplinary, involving teams of laser-mapping and data-managing computer scientists, entomologists, a score of assistants to install the numbered web strands. Although the cords are anchored in wall, floor or ceiling they derive some additional rigidity from the network of knotted intersections.

Alternately, the tensile forces involved in fiber fishtraps are explored at architectural scale in the beach shelters of Taiwanese Wang Wen-Chih. Fishtrap schematics also inform the Maori minimalism from Matt Pine of New Zealand, conveyed in elegant graphite drawings as well as steel models over seven feet.

Distinctions between planar and volumetric process may be demonstrated in a single work. Planar macrame serves as backdrop from Pennsylvanian Ed Bing Lee while the foreground is a three-dimensional object knotted in the round. Macrame relief juxtaposed to macrame volumetric. Other genres can be extended. Stitchbeading, usually planar in mesh forms, is able to exploit isometric pull in freeform without need of armature. This is demonstrated in geometric forms by Dustin Wedekind of California. The looping of crochet built spirally in my own work represents an analog predecessor to 3D printing, often in closed forms using elliptical geometry. Hyperbolic geometry undergirded the design of Illinois sculptor Jerry Bleem’s flag crochet. In addition to macrame, stitchbeading, and crochet, the over-under process of weaving is applied in indigenous traditions of volumetric works like the plaiting basketry of Joe Feddersen, Okanagan tribe Washington, and Solomon Battise, Couchatta tribe Louisiana. These artists paired volumetric simplicity with surface design. Geo Neptune, Passamaquoddy tribe Maine and Alberto Cruz, Tequisquiapan, Querétaro extend into unique formal concepts.

*

If fundamental differences in process have escaped notice in critical writings, as mentioned above there was a half-century veer toward material investigations that all but begged the question of construction processes. This arose when late 50s experimentation by loom-based artists trickled into group exhibitions. The artists had been shifting loom weaving from a mural approach to a relief approach. The incorporation of noncontinuous passages— intentional gaps— allowed new opportunities for composition. The scale of weavings grew.

Art institutions began to notice. A smattering of fiberwork exhibitions opened in the early 60s. Staten Museum, American Craft Museum were joined by the inaugural Lausanne Tapestry Biennial in 1962. The Swiss expo was to showcase artist-cartooned commissioned tapestries outsourced to French manufacturies but viewers were smitten with a room of heretofore unfamiliar Warsaw weavers who not only conceived but handworked their own compositions. Instead of transposed paintings, the Polish works were outsized, textural reliefs. Fiber combinations of various gauges, thin to thick, created nubby, even lumpy passages in the compositions. Abstractions had been adopted for surface incident. Palettes shifted toward natural fiber tones. Rather than standard color motifs, monochromes replaced figuration.

At this time experimentation was also flowing from the postBauhaus dispersion into Argentina, Black Mountain, Yale that imbued sculpture students with an enthusiasm for material investigations. Alternative fibers became fodder for experiments in plasticity and weight. Massive transit rope. Industrial felt. These experiments received attention at Manhattan’s Fishbach Gallery in 1966 and the Whitney’s Anti-Illusion exhibition of 1969. In these venues, such artists as Robert Rohm, Keith Sonnier, Robert Morris made explicit fiber statements about gravity, often in the context of gravitational experiments in modern choreography or decay experiments in musical composition.

An announcement that MOMA would mount a fiberwork exhibition in 1969 seemed like a pinnacle of recognition. The show’s curators certainly were knowledgeable enthusiasts of fiber art; there seemed a good deal of experimentation available from Eastern Europe, Scandinavia, Argentina, the US; the aforementioned Manhattan shows had generated critical writings. Process Art, Soft Sculpture, developments in weaving, all bode promising for the exhibition.

The show having opened, a review by Louise Bourgeois described the MOMA works, anticlimactically, as rarely transcending the decorative. The review noticed excessive two-dimensionality. It wondered whether the loom could allow any greater dimensionality. (With a background in the tapestry tradition in France, fiber webworks, stuffed textile totems, Bourgeois possessed experience relevant for this line of questioning.) She seemed to intuit possibilities of fiberwork sculpture unrealized by planar works.

Three years later an article in the periodical Craft Horizons posited that “filamental reality” called for flexible linking movements of knot or twist or loop to produce self-supporting constructions. The article, entitled Hard String, made entreaties for specifics in volumetric methods. The time seemed arrived that process might be recognized and taught, particularly the differentiation between planar and volumetric work.

Instead, after this point it became difficult to find any process mentions of fiberwork in the press or in exhibition catalogs. There was diminished institutional interest in the 70s. The Cleveland and National MoMA Kyoto museums mounted exhibitions and artist solos would surface from time to time while many of the volumetric innovators were shunted toward material culture rather than fine arts venues. Attention that did continue was focused on planar works that were related to textile arts like quilts or garment fashioning. The Lausanne Tapestry Biennial continued for only a dozen additional expos. Institutional commentary on sculpture types was decidedly slowing through the 70s, 80s, 90s.

*

Artist innovation during the remainder of the 20th century continued in a largely isolated rather than programmatic manner. Experimentation in planar works, process advances having largely been accomplished by midcentury, focused on pictorial compositions such as color juxtapositions (weavers James Bassler, Ed Rossbach), later on content emphasis like text or figurative political compositions in woven, beaded, or knit pieces. Some of these have been shaped with increasingly elaborate armature and heightened scale. Jeffrey Gibson (beading) and Nathan Vincent (crochet) provide 21st century examples.

In comparison, experimentation in volumetric works during these decades appeared even more random, being nonsystematically learned, far-flung, less included in general fiberwork exhibitions. The cumulative architectonics of the knot have in sculpture been approached idiosyncratically not programmatically; hyperbolic crochet has led to more advances in noneuclidian geometric proofs than in fine art practices, in-the-round macrame artists like Ed Bing Lee are difficult to locate. Nevertheless volumetrics can, with effort, be sifted from group exhibitions, from art fairs.

The works of Jorge Eielson of Peru satirized the euro-tightening of canvas on stretcher bars by tautening the textile into mounds of knots evoking the Andean tradition of quipu that had been ideologically eliminated by Catholic colonizers. The knot-based quipu language undergirded Eielson’s exhibitions at Venice Biennales in the 60s, in the 70s he centered knotworks into stage performances. Douglas Fuchs produced a range of twined fiberworks in seventies New York, a volumetric set of human-sized cones receiving notice in the craft press and grant boards that led to commissions for Australian public spaces. During this period Tadek Beutlich of Poland concluded his loom-based weaving years to experiment with handworked pieces, exploration that led him briefly to volumetric experiments. The many processes of basketry have been thoroughly engaged by John McQueen of New York over the decades following his mid70s MFA, and by New Mexico artist Michael Bailot Mendes in the 80s and 90s.

In the 21st century Miguel Angel Rojas of Columbia touched on the knot’s utilitarian history in his reclaimed, upcycled portion of roof thatching for purposes of spotlighting the usually anonymous, undercompensated nature of knotting. Uncredited practice has not discontinued in our current era. Employing unnamed makers for his retail line of totes and lampshades, Doug Johnston of New York focuses on coil basketry vessels based on compositions he once worked. More recently Joel Andrianomearisoa has incorporated into his textile installations knotted raffia sculptures made by his unnamed assistant in Madagascar Africa.

Others highlight the hands-on approach. Through performance art Paté Conaway of Illinois has created knit and crocheted works of unconventional materials in real time. Ramekon O’Arwisters of California incorporates volumetric aspects through a practice of binding tchotke fragments into crocheted mounds, sometimes in workshops. John Sims of Florida in a work titled The Hanging Of Knots Up To Eight Crossings used the components of tying to inspire others to explore the geometric possibilities of surface-building through accretion at the cellular level. Knot as building block.

From the Africa-bequest Gullah sweetgrass tradition of coiling, South Carolina native Antwon Ford has explored open forms attempting to perfect the elusive method of achieving the right angle in coiling. Dan Coopey of Brazil defies the painful byproduct of hard-fiber work, tendinitis, to create hollow closed-form sculptures inventively composed and displayed. He, like John McQueen, has been interested in natural sources of fiber, botanical facts informing his compositions. Japanese Kosen Ohtsubo arrives at installations from the direction of ikebana, composing in negative space to refer to extinction processes using botanical discards from the floral industry. Some photographers too have grasped parallels between nature’s and makers’ entwinements. Tlingit photographers Al Wakea-Nemish, Punch Oweect, Cal Kutkumaht captured vegetal forms. Ignatius Nzema, Ghana; Tyrese Dupree, Pennsylvania; Aloysius Blackmon, Guyana noticed manufactured happenstance.

Volkan Cirik of Czechia documents crochet that detours from garments into volumetric forms celebrating his social justice concepts. Newfoundland-born Dale Roberts extended the maritime netmaking of his village to create a range of abstracts in crochet, extending prosaic methods into aesthetic formalism. Antonio Pichilla of Guatemala is generally a planar fiberworker whose sculptures have led him incidentally to volumetric processes as he adapts Mayan cultural traditions into contemporary abstractions. Jose Perez Santiago of Illinois injects his glitz performance art into volumetric compositions, translating choreographic performances of coyness into vessel representations. Like Eielson, Santiago choreographs a knotting of human with object, offering social commentary on mainstream conventions.

Choreography enters less into capoeira dance, improvisational between paired practitioners. It has long roots in Bantu regions, while more recently it became associated with Afrobrazilian events. Offering martial arts practice, the performances that once allowed enslaved laborers to hone self-defense has developed into post-colonial social gatherings. Unlike the Pilobolus dance group that was formed by three Dartmouth men in 1971 featuring knotted configurations of human groups the capoeira events contain whip-like, sweeping motions of complementary pairs. Capoeira is accompanied by the berimbau, a stringed instrument.

The berimbau itself has longstanding indigenous traditions as well as 20th century nontraditional composer-players. They employ the instrument for its string tone as well as the percussive capabilities of the gourd resonator held against the torso. A benchmark musician would be Brazilian Nana Vasconcelos. On his 1980 album Saudades the track O Berimbau offers narratives of the instrument intertwined with European classical movements to compress the exigencies of Brazil colonialism into 19 elegiac minutes. Vasconcelos vocalized the melody to compatriot Egberto Gismonti who scored for Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra the movements that realize the slave perseverance Vasconcelos wished to memorialize. The a cappella track that serves as coda shifts the cultureshock to nontextual vocals. Scat serves as metaphor for occupation, vocal cords subbing for berimbau string. A chronicle of the Gordian knot that is the Portuguese era.

*

Knot again. The most recent revival, so to speak, of critical interest in fiberwork has circled from major institutional exhibition at Boston ICA to new books to a spate of twenties gallery mountings. Noteworthy that two well-conceived overview volumes, Fiber Sculpture 1960 to Present (2014) and Vitamin T: Threads And Textiles (2021) showed virtually uninterrupted planar entries. That they did not cover volumetric possibilities speaks to the sparsity of process vocabulary more than any lack of authorial effort. The artists in today’s essay attest this is a sculptural medium that not only awaits further innovation but is ripe for critiques that do make distinctions in process as much as in content.

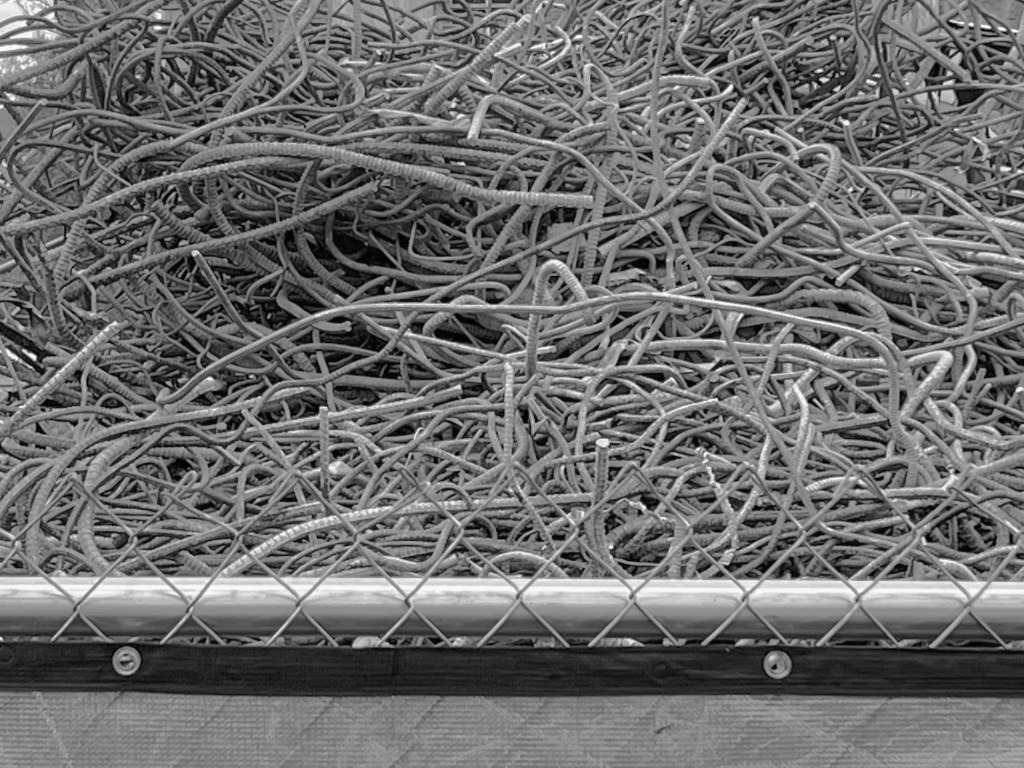

Cover image: Ed Bing Lee