Mud, by A.V. Port-Louis

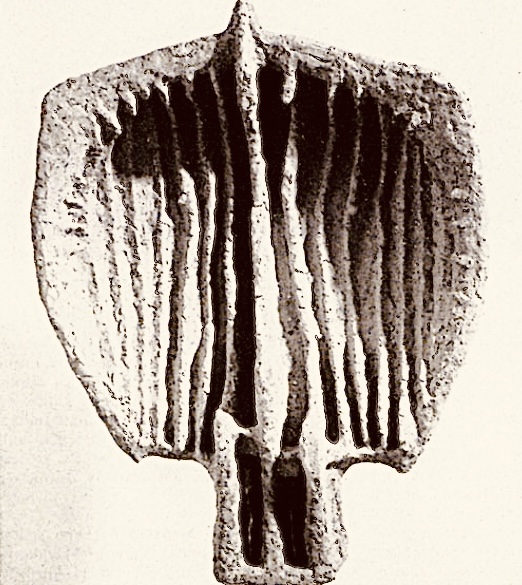

Gestural and constructed ceramics contribute a vital stream in art, the influence of modernism still flowing in fresh expressions more than a half-century after its emergence. A survey of ‘20s exhibitors reveals this vitality. The works are elemental. Desert spaces or moonscapes. Ocean floors or quarries. Meteors or Willendorfish stonecarved mother of us all. Ceramicist Bernard DeJonghe said “I’ve always been conscious of man being part of the mineral universe.”

Such clayness characterizes the works pictured above. They exhibit what in Japan is called tsuchi-aji, earth flavor. Their breadth of expression might to some extent be better comprehended with the aid of tentative categories, more important for the understanding of the viewer than the artist. Also helpful is the context in which these modernist expressions occurred.

At midcentury, movements toward modernist, sculptural approaches in ceramics emerged contemporaneously in several sites, among them London, Alfred New York, The US Pacific Northwest. Two of the vectors giving rise to the developments were restlessness with vessel pottery as well as influences by modernist, nonclay sculptors.

Art critic Raimund Stecker, in writing about clay sculptor Tony Deacon, notes that sculpture was liberated from representation by recording media about a century ago. Clay sculptor Tony Cragg notes that since then sculptors have liberated materials from the non-art world for use as a rich language expressing complex ideas and affect. The word liberated recurs for this postWar art development.

Having fled Nazis, London-resident Ruth Duckworth while at Central School Of Arts And Crafts created a 1950s series of expressionist ceramics. They were denounced by traditional potters. Critic Tony Birks lauded the “craggy, highly textured” pieces as work “one feels would grow out of the earth.” The 50s works earned her solo exhibitions by 1960 and commenced a life of clay creations. In 1964 she took a job at the University of Chicago during which time she expanded her styles.

Dan Rhodes of Iowa received an art degree at the University of Chicago. He took up pottery in 1941, which he taught at Alfred College in NY state since 1947. During the 50s he created expressionist ceramics that he said, in a 1958 interview, were “connected to what I find interesting in the world around us: the elemental surfaces of the mountains, valleys, eroded rocks, sand and beaches, river beds and glacial dumps, the muted colors of the rocks and minerals, the fire-memory which seems inherent in them.”

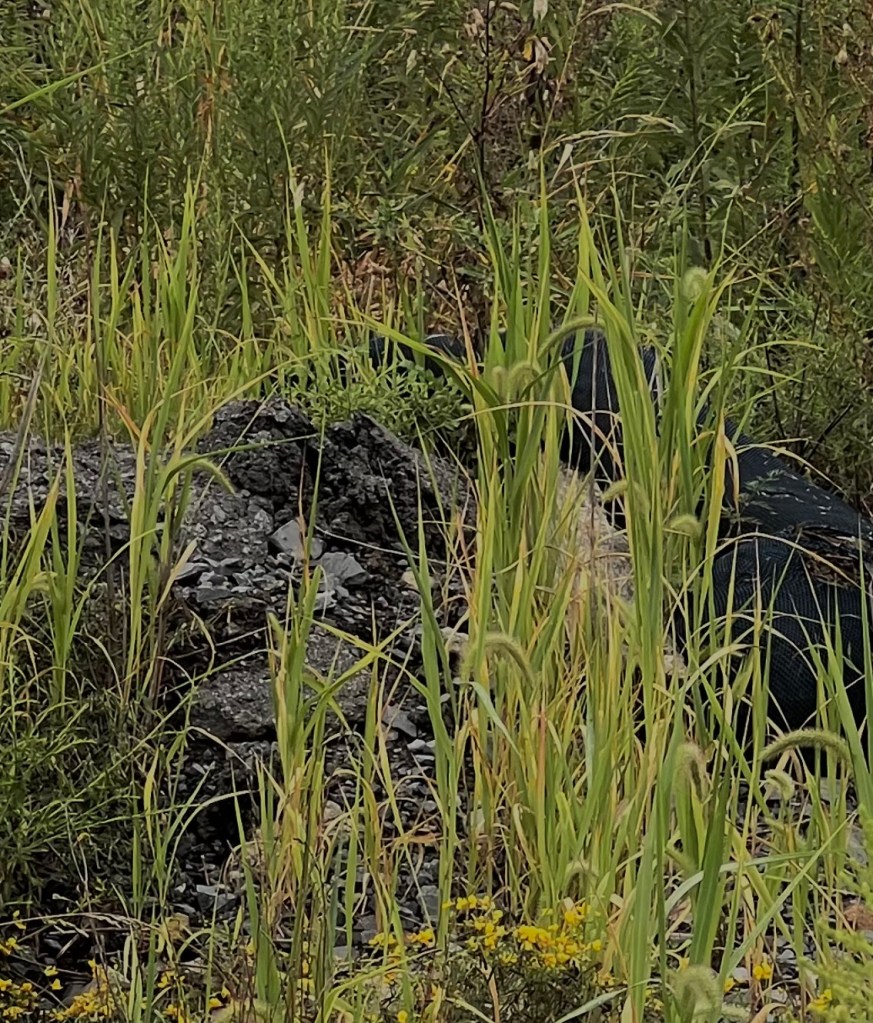

Betty Feves studied in postWar Manhattan at Columbia University and Art Students League. She took 50s modernist sculptural lessons to Oregon. Natural surfaces interested her, she sought direct responses to the clay and the firing. Alongside sculptural experiments in terra cotta she observed such landscape forms as basalt slabs and ovoid stones. “I was too much the farmer’s daughter, getting my hands dirty.” She dug clays and added gravel for texture and hue. She developed glazes from grasses and leaves.

These three innovated while other clayworkers, independently, explored similar aesthetics in Kyoto, Milan, and Los Angeles. Such gestural, modernist, nonvessel ceramics were not universally welcomed. Yet they remain a vigorous if overlooked pulse within 21st century fine arts. The materiality and process offer a primeval quality during progressively mechanical decades. That primeval matrix was an objective of the photo essay Mud & Kiln. Timorese undergrad Eufrasia Alves made an autumnal exploration of an appalachian university’s environs.

Amongst the gestural artists working currently, themes of erosion and sedimentation can be subject matter. Luke Fuller, UK, considers industrialization effects on landscapes while Londoner Shirley Nette Williams explores the mutual influences of nature on manufactured materials as well as chemical processes on natural resources, the nexus of urban and gaia. Gabriel Hartley, UK, is an abstractionist emphasizing texture; Jane Norbury, UK, is interested in the effects of liquids and heat on the outer shells of sculptures and humans.

Stonecarved aesthetics are relevant to Nesrin During, Turkey, in observiing the effects of weathering. Subtractive scuptural processes and negative space intrigue Javier Del Cueto, Mexico. Totemic and dwelling forms inspire Lucien Petit of France. Aging has been an interest of Jeremy Jernegan, Louisiana. Cross-Lypka of California produce, antidigitally, handworked objects emphasizing humanities.

Accretive work is reflected in the creased, accumulated forms of Yoshimi Futamura, Japan; also in the haptics of landscape forms recalled from the muscle memory of Bev Bell-Hughes, UK; as well as in geological time summoned in the multilayered pieces of Hiruma Kazuyo, Japan.

Within the sphere of constructive ceramics are smooth textures evoking ice by Leora Brecher, Pennsylvania; waveform patterns by Jeannine Marchand, Puerto Rico; componented outlines by Mincheng Wang, China, now studying at Alfred University.

Processes of painting and figuration feature in culturally specific installations by George Rodriguez, Pennsylvania, such as the contemplative retreat he created. José Sierra, Venezuela, applies Andean colorwork to precolumbian shapes. Yanina Myronowa, Poland, masters monument-scaled figurative ceramics.

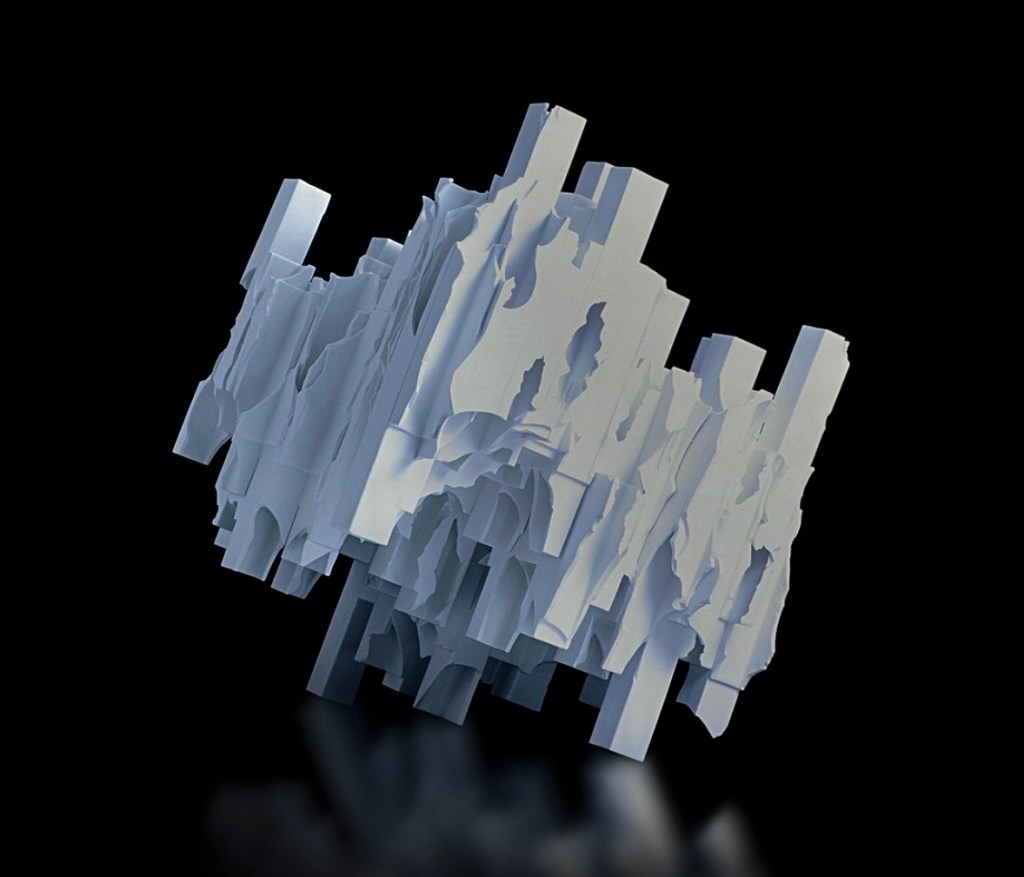

Composite elements make for multicomponent sculptures in such works as those by Berenice Hernandez, Mexico, in which blocks of clay are formed, cut, and reconfigured; by Mattia Vernocchi, Italy, that emphasize the human gesture; by Jacqueline Schapiro, Chile, where nature-inspired modules are combined. Gillian Lowndes, UK, makes assemblages of clay and nonclay mediums. Toni Ross, New York, has produced serial wall installations of earthworks. Ozioma Onuzulike, Nigeria, forms clay beads at different scales for assembly into relief work.

Slabwork has seen its exponents at Alfred University in New York, including Anne Currier whose calculus features masses and voids, and Paul Briggs, whose boxes abstract social influences on personality development. Slabwork shows vitality elsewhere: the reductive reliefwork of Anna Bella Papp, Romania; the shardlike crystalline growths of Kouzo Takeuchi, Japan; the serial oversized cube installations of Bosco Sodi, Mexico.

Aesthetics of Erosion is an elegant film depicting Yoshimura Toshiharu’s dedication to art; the ceramicist says “I often think the interiors of the kiln reflect the exteriors of our world, where unexpected transformations happen continuously”

Process and performance involving clay extends to ceramic artist Summer Hills-Bonczych. A maker of ceramic works spanning biomorphic forms and more euclidian assemblages, she appears in performance pieces with unfired clay. In the choreographed piece Murus an avatar buried in a clay wall is unearthed, vivified. The artist explains “as the wall is slowly and laboriously torn down by three women in workwear, the material of division becomes soft and changeable. Many things are buried in the oppressive stickiness of the clay which are, then, released and decontextualized, becoming tools of liberation and ceremonial renewal.”

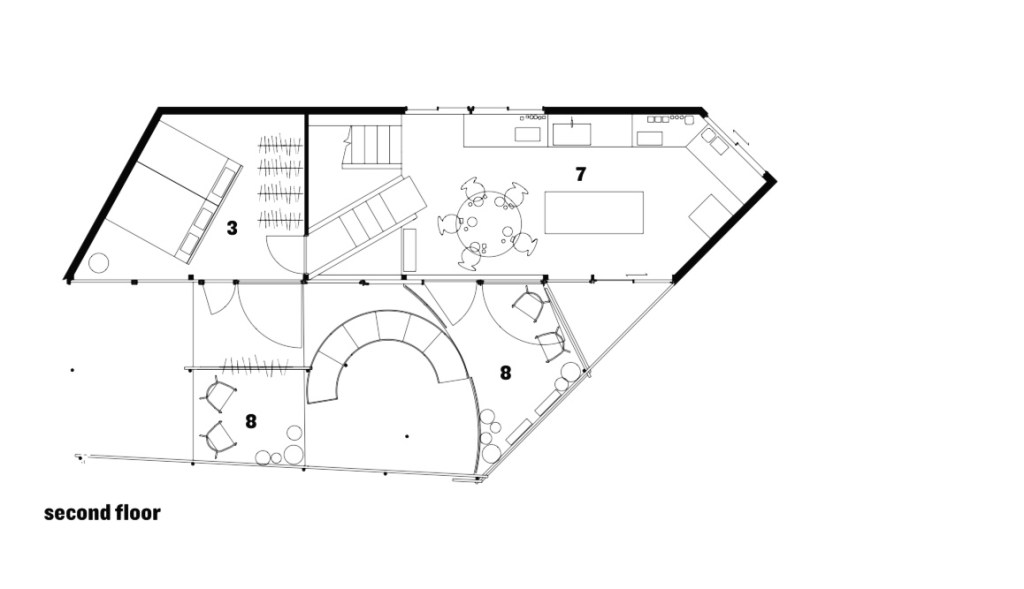

Earthwork in architecture takes a number of forms, including the literal forms for concrete pouring. An architect shaping concrete for interior space as much as exterior is Suzuko Yamada, Japan. Her conception of room use becomes fixed and sculptural, making volume, play of sunlight, sound travel her own. Some of her designs exhibited in 2012 at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum.

Composer David Lang, on So-Called Laws Of Nature: The instruments in the piece are not standardized. Most the performers must build themselves, giving every group a unique sound. “Scraps of wood, pieces of metal, clay pots— how the players shape the raw materials creates the piece’s sound world and tonality and feel,” Lang says. Player Adam Sliwinski described the debut recording involving “one movement of brash woodblocks, to fluttering canons of metal pipes and thundering drums, to the oddest, most melancholy chorale of tuned flowerpots, bells, and teacups.” Frank Olinski created the album cover with an image of hammer and ceramic cup. On composing, Lang notes that music is made of proportions and numbers. “Do the numbers generate a certain structure, creating the context and the meaning and the form, or are they just incidental byproducts of other, deeper, more meaningful processes?” Questions relevant to visual artists like ceramicists.

Cover image: Shirley Nette Williams

Verse: Marya Zaturenska translations and originals